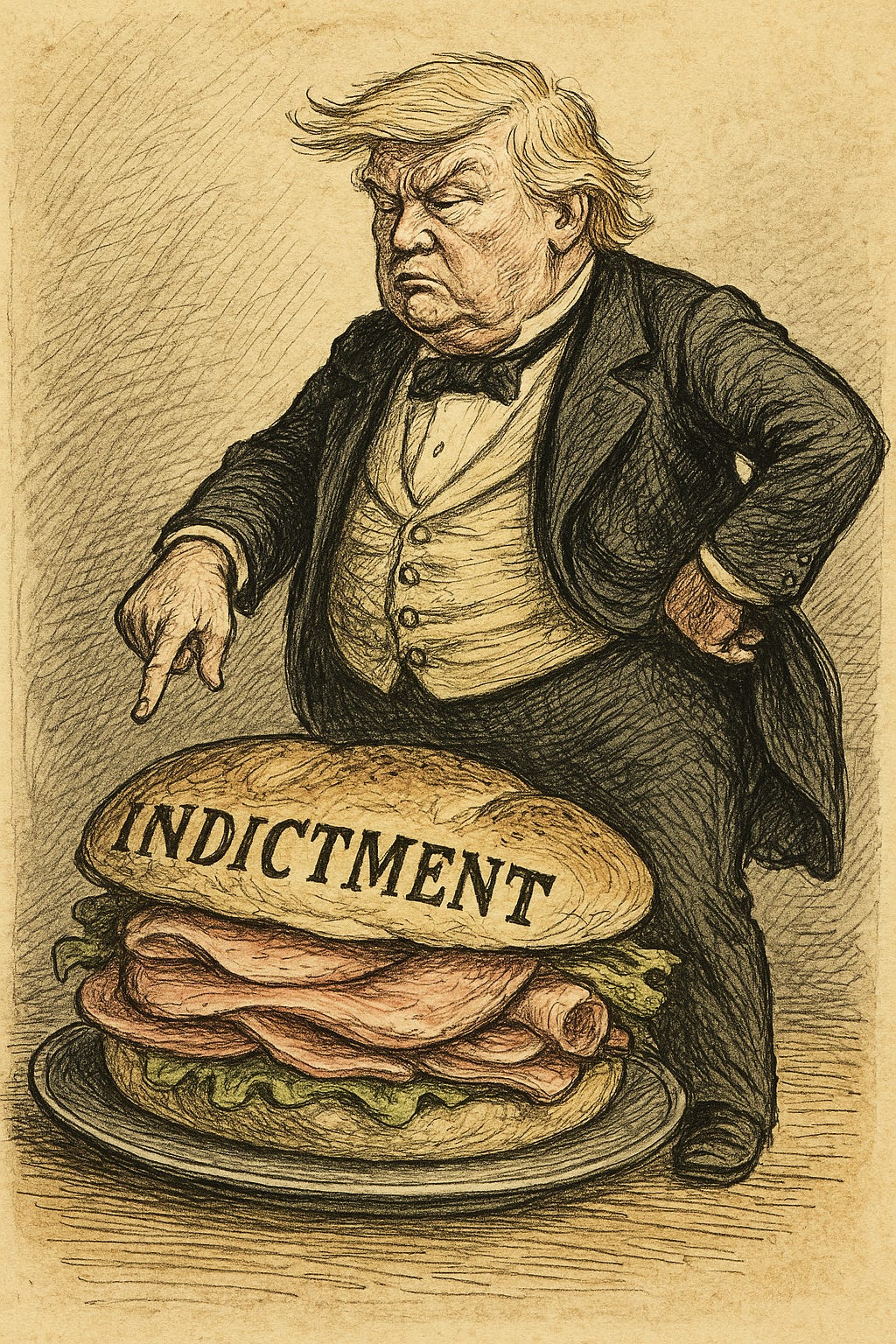

Becoming a Ham Sandwich

The Steady State | By Steven Cash, November 17, 2025

Judge Sol Wachtler, then Chief Judge of New York, famously quipped that a prosecutor could persuade a grand jury to “indict a ham sandwich.” For decades the line has been repeated as gospel truth by journalists, critics, defense lawyers, and even prosecutors themselves — a shorthand for the notion that grand juries are rubber stamps, indicting whatever a prosecutor puts in front of them. I spent years as a prosecutor in New York City — the “Law & Order” office — and presented hundreds of cases to grand juries in Manhattan. And for years, I argued that Judge Wachtler was wrong. The ham sandwich line is clever, but it’s misleading. It obscures more than it reveals.

Yes, grand juries indict most of the time. That part is true. But the implication — that grand jurors mindlessly rubber-stamp whatever the prosecutor lays before them — does not match the reality of a well-functioning criminal justice system. The deeper truth is simpler: by the time a case reaches a grand jury, it has already passed multiple filters that screen out weak, sloppy, or unjustified charges.

Why Grand Juries Indict

Start with the legal standard. An indictment requires probable cause. That is the same standard required for the initial arrest. A low rung on the ladder of proof — but that does not mean there are no rungs beneath it. In New York, and in most jurisdictions, cases encounter several layers of scrutiny before anyone steps into a grand jury room:

The arresting officer must believe probable cause exists. This is not trivial — officers know their decisions will be reviewed.

In many cases, a judge reviews the basis for the arrest at arraignment.

Most importantly, prosecutors evaluate the case. And prosecutors rarely use the bare probable cause standard when deciding whether to seek an indictment.

The best offices — like the one I served in under the legendary Robert M. Morgenthau — ask far more demanding questions: Is the defendant actually guilty? Can we prove it to a jury beyond a reasonable doubt? Should this case be brought at all?

The grand jury indicts so oftenbecause it sees only cases that have already survived multiple layers of scrutiny. That pipeline works only if all the actors in it care about truth, fairness, and justice. Officers must investigate honestly. Agents must gather facts rather than manufacture them. Prosecutors must exercise judgment rather than ambition. Supervisors must encourage restraint rather than reward headlines. Leadership must prioritize ethics over politics. And yes, abuses have occurred in every system. But the structure — and the culture — of American prosecution has historically relied on layers of independent judgment. During those years, and later as a staffer on the Senate Judiciary Committee overseeing the Department of Justice, I saw a system that worked precisely because so many people in it cared about getting it right.

What the Trump Era Broke

But I find myself rethinking Judge Wachtler’s ham sandwich.

Not because he was right about grand juries — he wasn’t — but because the protections that once made his quip wrong are being dismantled. In the federal system under Donald Trump, prosecutions no longer arise primarily from street arrests, careful investigations, or evidence-based decision-making. They arise from the whims, resentments, and social-media impulses of a president who openly views the justice system as a tool of personal vengeance.

In this environment, the test for prosecution is not: “Has this person committed a crime — can we prove it? It is: Is this person an enemy of the president or his allies? Professional leadership has been replaced with loyalists whose chief qualification is their willingness to please the boss. Prosecutors no longer operate under the guiding ethic that the power to charge is sacred. They operate under pressure — explicit or implicit — to deliver results that align with political desires.

Investigators, likewise, are bent toward service to power rather than service to the truth. It looks eerily familiar to what I saw in my later career at the CIA, studying autocratic regimes overseas: well-dressed lawyers playing the role of prosecutor while behaving like mob enforcers; agents whose job is not to seek justice but to satisfy the ruler’s expectations. A justice system repurposed into a weapon.

In U.S. v. Comey, Judge Fitzpatrick’s blistering opinion earlier this week excoriating the Department of Justice is only one instance of courts recognizing what is happening: this is not normal. This is not American justice as we have known it.

The Ham Sandwich Returns

And so I find myself circling back reluctantly — not to Judge Wachtler’s meaning, but to his imagery. If the President marks you as an enemy, the safeguards collapse. If the Attorney General is a loyalist, the filters vanish. If investigators serve power rather than truth, the starting point is corrupted. If prosecutors view themselves as soldiers rather than ministers of justice, then probable cause is no longer a standard — it’s a technicality.

We live now in a system where becoming a “ham sandwich” is no longer a joke. It is a real possibility for anyone the president chooses to target. And that is not a failure of grand juries. It is the failure of a system whose safeguards are being deliberately destroyed — the people, the culture, the ethics — have been eroded by a president who believes justice exists to serve his will. If you are perceived as the enemy of the President, you may indeed be a ham sandwich.

Steven A. Cash served as a former prosecutor in the Manhattan District Attorney’s office before joining the CIA in 1994 as Assistant General counsel and subsequently serving as an intelligence officer in the Directorate of Operations. In 2001 he joined the Senate Select committee on Intelligence as Counsel and designee-staffer to Senator Diane Feinstein). He later served as a senior staffer in the House Select Committee on Homeland Security, the Department of Energy, the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Terrorism, Technology and Homeland Security and the Department of Energy. In the private sector he has advised on national security, counterintelligence, and technology policy and served on the Biological Sciences Experts Group under the Director of National Intelligence. Mr. Cash is currently the Executive Director of The Steady State.

Founded in 2016, The Steady State is a nonprofit 501(c)(4) organization of more than 360 former senior national security professionals. Our membership includes former officials from the CIA, FBI, Department of State, Department of Defense and Department of Homeland Security. Drawing on deep expertise across national security disciplines including intelligence, diplomacy, military affairs and law, we advocate for constitutional democracy, the rule of law and the preservation of America’s national security institutions.

This is one of the many reasons why 40% of women ages 15-44 said they wanted to leave the US for good if they could. I know some of the women who have already left.

https://news.gallup.com/poll/697382/record-numbers-younger-women-leave.aspx

I have to say that this talk about Grand Juries and Ham sandwiches might, possibly, be construed as unfair disparagement of “ham sandwiches.” Just sayin’!!!