Distorting the Human Rights Report Undermines US Strategic Interests

The Steady State | Annie Pforzheimer

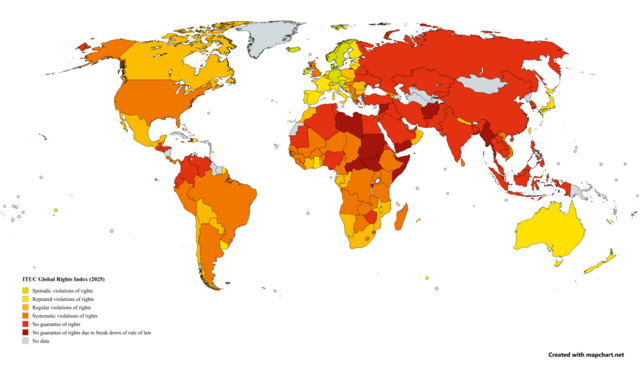

Global Rights Index 2025

The Human Rights Report is not a feel-good exercise driven by unbounded idealism; when researched correctly and reported without prejudice, it serves a unique and strategic purpose of keeping the government aware of simmering dissent and regime instability.

In one more act of systematic gutting of traditional and proven tools of foreign policy, the Trump Administration turned the annual US Country Reports on Human Rights into a parody.

Since its inception decades ago, the report has been changed and expanded, following political requirements set by Congress. It has become a well-respected document of record, often used to arbitrate refugee and asylee claims, and its statutory basis is unquestioned. The practice of preparing an annual, world-wide human rights report to Congress dates to 1974, when it was mandated under the US Foreign Assistance Act out of concern that US Cold War allies were engaging in gross violations of human rights, using US-supplied military equipment and training. The report is framed by the 1948 UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights (a brainchild of Eleanor Roosevelt), itself inspired by the US Constitution’s Bill of Rights.

What happened in 2025 under the Trump Administration to these ideals? First, references to women’s rights, and those of LGBTQ people, were widely gutted. Those issues not only are important in their own right, they also demonstrate how a regime treats any marginalized group. Secondly, some countries’ serious human rights abuses were glossed over. For El Salvador, the report stated that “There were no credible reports of significant human rights abuses.” How convenient for that supposed dearth of reporting that El Salvador recently kidnapped a leading human rights advocate whose organization, Cristosal, has gone into exile – meanwhile, El Salvador is jailing US deportees. And finally, the report gratuitously criticizes countries currently being targeted by the Trump Administration – like Brazil and South Africa – for offenses they blatantly overlook elsewhere.

These issues are not for history books and academics. They touch human lives and US national security. They are immediately relevant to people from these nations being forced to return to danger and even death, when their protected status is terminated by the Department of Homeland Security. And the report is not a feel-good exercise driven by unbounded idealism; when researched correctly and reported without prejudice, it serves a unique and strategic purpose of keeping the government aware of simmering dissent and regime instability.

In my own thirty-year State Department career, I worked on the report in six countries, in a variety of capacities. I know the deep professionalism needed to create them, and the strategic purpose they should be playing in promoting our values and our security. The human rights report process makes it a functional requirement that embassies have an open channel of communication with the most disgruntled elements of society, and that senior officials in the Embassy and in Washington are aware of these groups’ complaints. One historical case demonstrates the pitfalls when this is ignored. In Iran, before the 1978 revolution, junior Embassy officials with excellent local language skills tried to sound the alarm about religiously conservative students who disliked the Shah’s secularism and corruption, but their attempts to report these facts to Washington were shut down by the Ambassador. As a result, the US was effectively blindsided, with massive strategic implications.

Only accurate reporting will lead to good policy. While some of my fellow diplomats found the prospect of criticizing a friendly government uncomfortable, what was essential was understanding and reporting the objective facts on the ground. In Turkey the draft report was nearly 70 pages long. To research it, I met those there who had braved torture to continue to fight for their rights – including a Kurdish doctor who carefully documented his own extensive injuries, to make his suit against the government stand up in court. In South Africa, anti-apartheid activists explained to me that throughout the 1980’s, when their press censored all criticism of the whites-only government, the annual publication of the US Human Rights report was the only time these issues were in the media – because the newspapers had to run something published by the US government.

The international architecture on which our relatively peaceful post-World War II era was built relies on hard and soft power, including support for international norms that history has shown can usher in stability. Chief among these norms are basic human rights, especially the ability of citizens to be treated fairly and humanely by their government. Without this guarantee, violent unrest is more likely. The Human Rights Report matters on an individual level – no one should be forced back to a country which will torture, imprison, and kill them. It matters because US prestige rests in part on our appearance of impartiality, a difficult but worthy goal. And finally, our adherence to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights matters to the international order we helped to create.

Annie Pforzheimer is retired senior U.S. diplomat, an adjunct professor of international relations at the City University of New York and Pace University, Adjunct Fellow at the Center for a New American Security, and a consultant, researcher, and public commentator on foreign policy. During her 30-year career she served as Acting Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Afghanistan and Deputy Chief of Mission in Kabul, the Director for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement at the US Embassy in Mexico City, and Director for Central America Engagement in the National Security Council. She is a member of The Steady State

Founded in 2016, The Steady State is a nonpartisan, nonprofit 501(c)(4) organization of more than 300 former senior national security professionals. Our membership includes former officials from the CIA, FBI, Department of State, Department of Defense and Department of Homeland Security. Drawing on deep expertise across national security disciplines including intelligence, diplomacy, military affairs and law, we advocate for constitutional democracy, the rule of law and the preservation of America’s national security institutions.

This is written with commendable moral authority, based on experience. I was a congressional aide when the first State Department human-rights report came out. After the scandals of the Vietnam War (LBJ) and Watergate (Nixon) it was refreshing to see American diplomacy return to our postwar moral high ground. Now America’s political leaders have turned their backs on international human rights norms. I don’t think that a pure demagogue like Donald Trump knows better. But our secretary of state does.