One of Donald Trump’s early executive orders was to end birthright citizenship for children born to undocumented immigrants. This has sparked a national debate that further deepens the partisan divide, threatening the American democracy as we know it.

What is birthright citizenship?

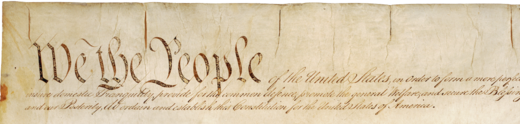

The Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution grants birthright citizenship. The concept of birthright citizenship in the U.S. has its roots in English common law, which holds that any person born within the dominion of the Crown was a natural-born subject. The colonies adopted this principle, and it was later incorporated into the national government when the republic was founded.

The Fourteenth Amendment was not arrived at without some controversy and compromise. During Reconstruction, it became apparent that additional legal measures were necessary to protect the rights of freedmen, and Congress decided to amend the Constitution to grant them citizenship, thereby theoretically protecting them from discriminatory state laws. Debate over the amendment raged over issues of states’ rights and the meaning of citizenship and equal protection under the law, leading to several alterations and compromises in the original text. The desire to find common ground for the reunification of the country after the devastating Civil War, for instance, led to the granting of suffrage to freedmen being dropped. The debate over the specific meaning of ‘equal protection’ continues to be a point of contention, as exemplified in a debate where a member of Congress discussed the unequal treatment of married women regarding property ownership, which varied from state to state until the mid—twentieth century.

Pros, Cons, and Possible Consequences

Controversy over the meaning and intent of the Fourteenth Amendment didn’t end with its adoption. Some of the same arguments raised in the 1860s are still being raised today, echoing or foreshadowing the president’s executive order.

One argument against the granting of birthright citizenship to the children of undocumented aliens is that it is erroneous to believe that anyone present in the U.S. is subject to the jurisdiction of the United States. The argument itself is erroneous since court cases and government regulations are clear that foreign diplomats are ‘not subject to the jurisdiction of the United States.’ Tourists and undocumented aliens, on the other hand, have been declared to be subject to the jurisdiction of the United States by over a century of Supreme Court decisions.

The executive order has been temporarily blocked by a federal judge, who called it ‘blatantly unconstitutional.’ The supporters of these efforts seem to be depending on the right-leaning Supreme Court to be on their side, but that court has not yet rendered a decision.

Those supporting the executive order argue that it would reduce incentives for illegal immigration, protect national sovereignty, and ensure fairness and equity. They further argue that the U.S. alone grants birthright citizenship. They fail, though, to offer evidence in support of their views and overlook the challenge to the Constitution. Their efforts to redefine the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment to make it fit their views on what an ‘American’ is have an unfortunate resemblance to arguments advanced in the 1800s that described those of Asian descent as less eligible for American citizenship than Europeans.

Pros, Cons, and Possible Consequences

Those supporting the Heritage Foundation’s proposals on birthright citizenship argue that it would reduce incentives for illegal immigration, protect national sovereignty, and ensure fairness and equity. They also argue that we are alone in granting birthright citizenship.

In advancing these arguments, however, they offer no supporting evidence and overlook the potential consequences, beginning with the challenge to the very foundation of our democracy —the Constitution. Their efforts to redefine the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment to make it fit their views on what an ‘American’ is have an unfortunate resemblance to arguments advanced in the 1800s that described those of Asian descent as less eligible for American citizenship than Europeans.

Also overlooked is the humanitarian disaster that such an action would cause. No mention is made, for example, of the time frame of implementing such a change, provided the Supreme Court doesn’t kill it outright. Will it be retroactive, and if so, how far back would it go? If, for example, children born to aliens in the country on student visas will be found ineligible for automatic citizenship, will Kamal Harris’s citizenship be revoked? What happens if no other nation claims them as citizens? Do they then become a stateless population within the United States?

In 2019, it was estimated that 5.5 million children in the United States under age 18 lived with at least one parent in the country illegally, representing seven percent of that demographic in the population. When those over 18 are added to the mix, assuming the authors of this move push for maximum hardship, the United States could see itself joining the ranks of countries like Bangladesh, Côte d’Ivoire, Myanmar, and Thailand. The U.S. would surpass Bangladesh’s 972,000 with children under 18 alone. There are also potential negative consequences for the rest of the nation. A larger marginalized population could destabilize neighborhoods, especially low-income neighborhoods, and disrupt the labor force. This latter issue is particularly acute in the agricultural industry, which depends heavily on immigrant labor. Disruptions there will be felt on every American’s grocery bill.

Eliminating birthright citizenship, in effect, tanking the Fourteenth Amendment, changes the fundamental nature of our society. We would no longer be the nation we claim to be, the shining city on the hill. We should ask ourselves if this is the kind of country that we aspire to be. We become that country by upholding the principles of equality and inclusion that are embodied in the second paragraph of the Declaration of Independence, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that their Creator endows them with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.’

Charles A. Ray spent 20 years in the U.S. Army with two tours in Vietnam. He retired as a senior US diplomat, serving 30 years in the U.S. Foreign Service, with assignments as ambassador to the Kingdom of Cambodia and the Republic of Zimbabwe, and was the first American consul general in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. He also served in senior positions with the Department of Defense.

Founded in 2016, The Steady State is a nonpartisan, nonprofit 501(c)(4) organization of more than 290 former senior national security professionals. Our membership includes former officials from the CIA, FBI, Department of State, Department of Defense and Department of Homeland Security. Drawing on deep expertise across national security disciplines including intelligence, diplomacy, military affairs and law, we advocate for constitutional democracy, the rule of law and the preservation of America’s national security institutions.