The Fourth Amendment Was Built to Stop Fear — Not Just Bad Evidence

The Steady State | by Steven A Cash

The Fourth Amendment is one of the most celebrated protections in the American Constitution. It promises that the government will not subject people to unreasonable searches and seizures. Yet for most of modern American history, that promise has been enforced in a surprisingly narrow way: through the exclusionary rule. In broad strokes, when the government violates the Fourth Amendment while gathering evidence, that evidence cannot be used against the person in court.

For decades, this rule did much of the real work. Police officers, FBI agents, and prosecutors learned a simple lesson early in their careers: conduct an unlawful search, and you risk losing the case. Warrants, probable cause, and carefully defined exceptions were not abstract legal doctrines. They were practical constraints.

But that system only works if the government is actually trying to build a case. For most of American history, it was.

Today, in some of the most consequential uses of federal power, it isn’t.

How the Fourth Amendment Is Usually Enforced

The Fourth Amendment itself contains no enforcement mechanism. It states a legal principle, not a penalty. The exclusionary rule was created by courts to fill that gap: the government should not be permitted to benefit from violating the Constitution.

Alongside exclusion, civil lawsuits were meant to provide a backstop. But those remedies have always been weak. Even when plaintiffs succeed, damages are paid by taxpayers, not by the officers who violated the law. Over time, the Supreme Court has further limited accountability—most notably by narrowing claims under Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents and expanding qualified immunity.

In practice, exclusion became the Fourth Amendment’s teeth. If evidence mattered, legality mattered.

That Was Never the Founders’ Only Concern

This modern, criminal-procedure framing misses what originally terrified the Founders.

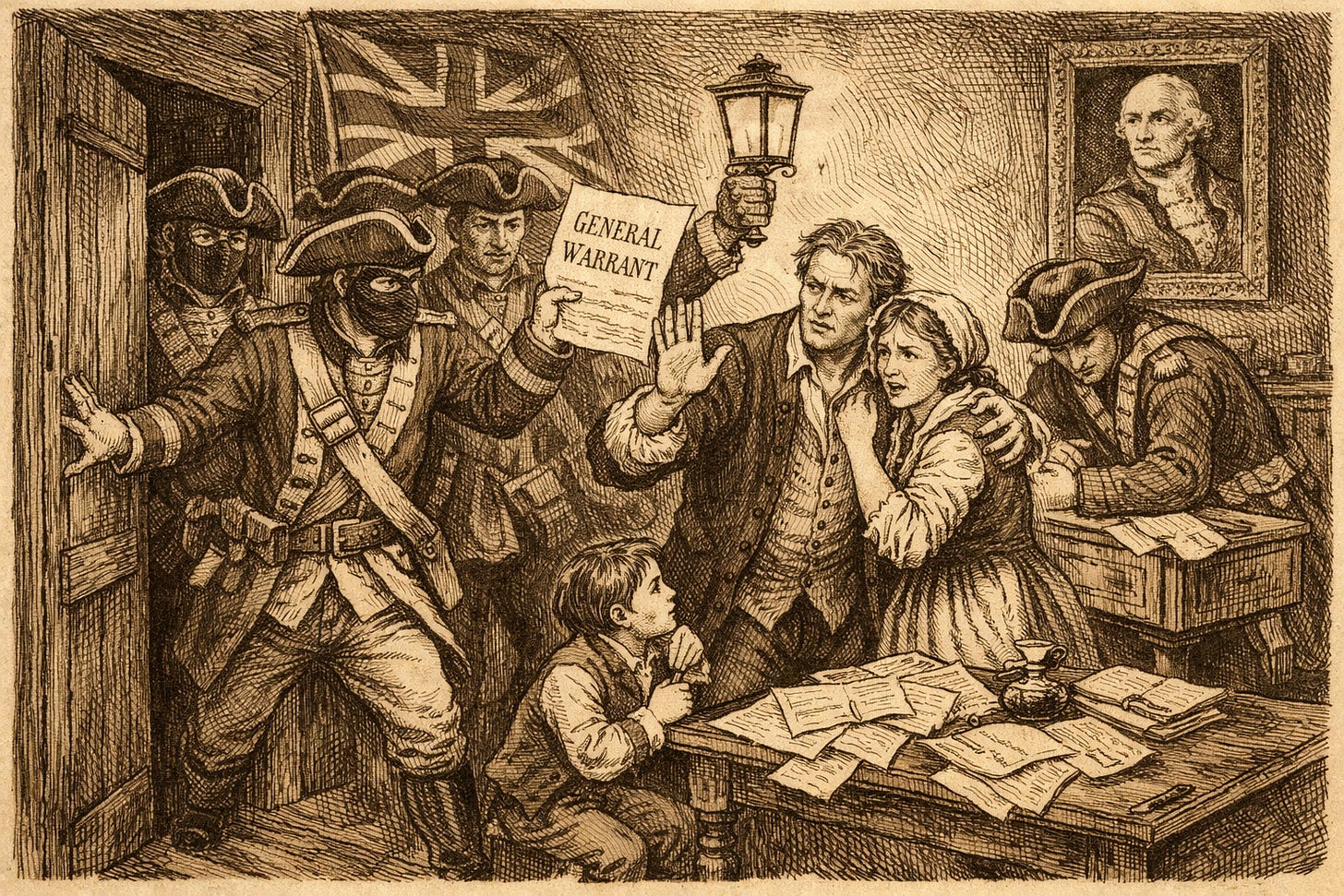

The Fourth Amendment was a direct response to the British Crown’s use of general warrants and writs of assistance—open-ended search authorities that allowed officials to search anyone, anywhere, without individualized suspicion. These searches were not always about prosecuting crimes. They were about asserting dominance and keeping the population compliant. The King used these writs not to “take care that the law” be enforced, but to preserve and protect his throne.

No one articulated this danger more vividly than James Otis, whose 1761 essay Against Writs of Assistance warned:

Every one with this writ may be a tyrant; if this commission be legal, a tyrant in a legal manner also may control, imprison, or murder any one within the realm. In the next place, it is perpetual; there is no return. A man is accountable to no person for his doings. Every man may reign secure in his petty tyranny, and spread terror and desolation around him. In the third place, a person with this writ, in the daytime, may enter all houses, shops, &c. at will, and command all to assist him. Fourthly, by this writ not only deputies, &c., but even their menial servants, are allowed to lord it over us. Now one of the most essential branches of [our] liberty is the freedom of one’s house. A man’s house is his castle; and whilst he is quiet, he is as well guarded as a prince in his castle. This writ, if it should be declared legal, would totally annihilate this privilege. …

Otis was not worried about “tainted” evidence. He was worried about fear—about a government that could intrude at will, without explanation and without consequence, into a person’s home, papers, and private life.

That concern runs throughout the Federalist Papers. The authors repeatedly emphasized that liberty depends on constraining discretionary power before it is abused, not merely punishing it afterward. The Fourth Amendment was meant to prevent the government from roaming through the population untethered from specific suspicion and judicial oversight.

In short, the Amendment was designed to prevent intimidation, not just bad prosecutions.

For much of American history, federal law enforcement operated within a criminal framework. Searches and arrests were typically tied to investigations that might end up in court. Under those conditions, the exclusionary rule worked. An unlawful search could sink a case, embarrass a prosecutor, and derail a career.

That incentive structure shaped behavior—but it depended on one crucial assumption: that the government cared whether evidence would later be admissible.

Current Immigration Enforcement Breaks the Model

Immigration and Customs Enforcement often operates outside that assumption.

ICE agents, acting more as paramilitaries than police, are not seeking evidence to present to a jury—or even to a court. Removal proceedings are administrative, with weaker procedural protections and limited suppression remedies. Many enforcement actions never meaningfully reach any adjudicative forum at all. In numerous cases, the search and detention appear to be the end goal—instilling fear and uncertainty rather than building a legal case.

In this environment, the exclusionary rule has little deterrent effect. An unlawful stop, search, or arrest does not “lose the case” because there is no case to lose. The immediate objectives—detention, disruption, signaling, fear—are achieved regardless of legality. In criminal cases, evidence derived from an unlawful arrest is excluded. But when evidence is not the objective, exclusion is irrelevant. Nor do civil lawsuits meaningfully constrain conduct. Agents face minimal personal risk, and any damages are borne by the public. This protection is enhanced by the use of military, instead of police, tactics – masked paramilitaries, wearing tactical gear, and operating in large military formations.

The result is a profound asymmetry: the Fourth Amendment still exists on paper, but its enforcement mechanism is disconnected from how power is actually exercised.

When Fear Replaces Evidence

This is not simply a story about immigration policy or rogue officers. It is a story about a government stepping outside constitutional norms—into a world where fear, not evidence, is the instrument of power. The Fourth Amendment was designed to prevent exactly this scenario. General warrants were dangerous not because they produced unreliable evidence, but because they placed the population under constant threat of arbitrary intrusion.

When government agents are engaged not in law enforcement but in intimidation and control, the traditional tools of Fourth Amendment enforcement are blunted. The Constitutional language is there, but ignored, and, from the perspective of this Administration and its paramilitary arm, irrelevant.

Unless courts or Congress develop ways to impose real consequences for unconstitutional searches and seizures outside the criminal-trial context, the Fourth Amendment risks becoming what James Otis feared in another form: a right proclaimed, but not protected.

The Administration often justifies aggressive, extra-constitutional actions by ICE and other elements of the expanding “security services” as reflecting the “will of the voters.” There is at least some truth to that claim. And the will of the voters still matters, and there will be a chance for that will to be expressed in the coming mid-term elections.

A promise honored in theory—and hollow in practice.

Steven A. Cash served as a prosecutor in the Manhattan District Attorney’s office before joining the CIA in 1994 as Assistant General counsel and subsequently serving as an intelligence officer in the Directorate of Operations. In 2001 he joined the Senate Select committee on Intelligence as Counsel and designee-staffer to Senator Diane Feinstein). He later served as a senior staffer in the House Select Committee on Homeland Security, the Department of Energy, the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Terrorism, Technology and Homeland Security and the Department of Energy. In the private sector he has advised on national security, counterintelligence, and technology policy and served on the Biological Sciences Experts Group under the Director of National Intelligence. Mr. Cash is currently the Executive Director of The Steady State.

Founded in 2016, The Steady State is a nonprofit 501(c)(4) organization of more than 360 former senior national security professionals. Our membership includes former officials from the CIA, FBI, Department of State, Department of Defense, and Department of Homeland Security. Drawing on deep expertise across national security disciplines, including intelligence, diplomacy, military affairs, and law, we advocate for constitutional democracy, the rule of law, and the preservation of America’s national security institutions.

The recent resignation of 6 DOJ attorneys as conscientious objection to the 47 maladministration’s unconstitutional actions honor Attorney, James Otis’ leadership in the 1750s & 60s. Mass was chartered in 1629 as a private corporate venture by Royal Charter but they left England with the original document & had been operating with greater independence than other colonies for 120 to 130 before Otis resigned his post as attorney for The Crown to argue on behalf of the Boston Colony. He’s largely attributed as developing the language to describe & argue for Natural Rights and the rights to autonomy for people in the colonies. <> A related aside: The geography & natural resources of colonial Mass enabled it to dominate colonial commerce in foreign trade. The 1) maritime & 2) maneuvering for independence & 3) market share in global trade histories of Boston until the age of steam & railroads reads like a novel.

Really interesting read... How many of our early laws and rules are "new again?"