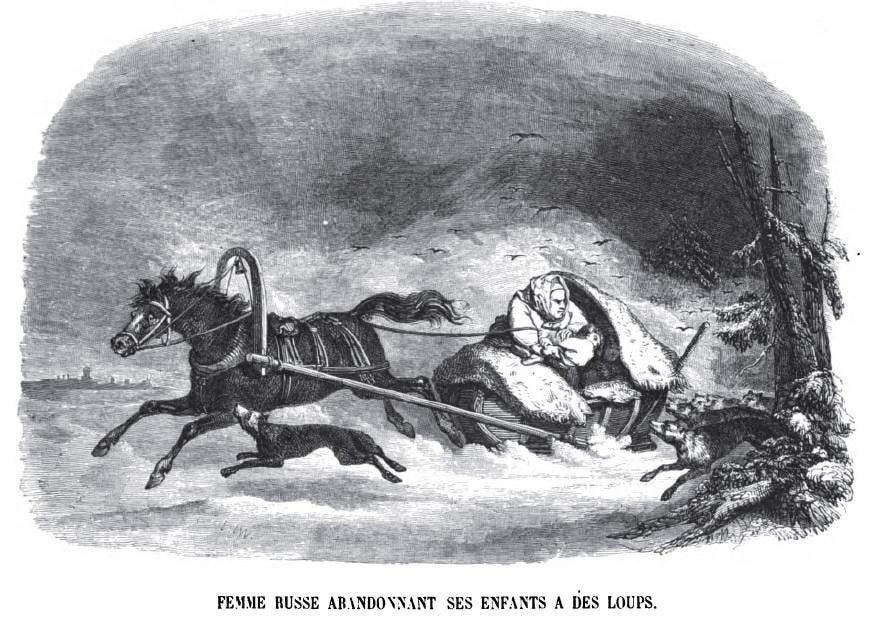

Throwing to the Wolves

The Steady State | by Steven A. Cash

Autocrats and dictators demand loyalty as a one-way obligation. They insist on personal fealty from aides, allies, and supporters, but they almost never return it. In authoritarian systems, loyalty flows upward, while blame flows downward. When events go wrong, the autocrat survives by sacrificing those beneath him. When the autocrat thinks the wolves get too close, he throws them aside in sacrifice

This is not a flaw in the system; it is the system. Autocrats deliberately cultivate a surplus of cronies: officials, enforcers, spokespeople, and “friends” who are useful precisely because they are disposable. Each is encouraged to push boundaries, take risks, or carry out aggressive acts on the leader’s behalf. And each knows, whether explicitly or intuitively, that protection lasts only as long as usefulness. When consequences arrive, the autocrat steps back, expresses surprise or concern, and lets the underling take the fall.

Blame, in this model, is a resource to be managed. By allowing subordinates to overreach, the autocrat creates plausible scapegoats. If the gamble succeeds, the leader claims credit. If it fails: if violence escalates, public outrage grows, or legal exposure appears, the leader disavows, condemns, or quietly discards the very people who acted in his name. The cronies are not betrayed; they are consumed, exactly as intended.

This dynamic is on display again and again in modern authoritarian politics, and Donald Trump is a master practitioner of it. He rewards loyalty rhetorically, encourages aggressive behavior implicitly and explicitly, and then distances himself the moment that behavior becomes politically costly. Officials who “went too far” suddenly acted alone. Allies who followed the tone and direction he set are recast as rogue actors. Responsibility is atomized; authority remains centralized.

Watch how this pattern plays out in moments of crisis. The leader stokes the fire through rhetoric, pressure, or deliberate ambiguity. When the flames rise, his cronies are left holding the match. And when the heat threatens to spread upward, he reenters the scene as a supposed stabilizer, casting himself as the one person capable of restoring order. He becomes, in his own telling, the savior of a disaster he helped create.

This is why loyalty to an autocrat is always misplaced. It is never reciprocal, never secure, and never rewarded in the long run. In authoritarian systems, friends are tools, supporters are shields, and expendability is not a risk; it is the job description. This brutal cycle of blame and avoidance is bad for everybody, but most importantly, for the American people.

Steven A. Cash served as a prosecutor in the Manhattan District Attorney's office before joining the CIA in 1994 as Assistant General counsel and subsequently serving as an intelligence officer in the Directorate of Operations. In 2001 he joined the Senate Select committee on Intelligence as Counsel and designee-staffer to Senator Diane Feinstein). He later served as a senior staffer in the House Select Committee on Homeland Security, the Department of Energy, the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Terrorism, Technology and Homeland Security and the Department of Energy. In the private sector he has advised on national security, counterintelligence, and technology policy and served on the Biological Sciences Experts Group under the Director of National Intelligence. Mr. Cash is currently the Executive Director of The Steady State.

Founded in 2016, The Steady State is a nonprofit 501(c)(4) organization of more than 360 former senior national security professionals. Our membership includes former officials from the CIA, FBI, Department of State, Department of Defense, and Department of Homeland Security. Drawing on deep expertise across national security disciplines, including intelligence, diplomacy, military affairs, and law, we advocate for constitutional democracy, the rule of law, and the preservation of America’s national security institutions.

This is why getting rid of Noem, if it happens, would be a relatively insignificant tidbit. Necessary, and important in itself, but hardly sufficient.

A beautiful piece of analysis and exposition. The critical lens necessary to apply to our current leadership, and those of a similar ilk.